To Boldly Go: Sonic Cowboys and the God of Change

Lessons in Shapeshifting from Andre 3000, Yves Tumor, Deafheaven, and SASAMI

In one of the first editions of Another Thought, I wrote about this quote from Brian Eno that still occupies my mind. He says:

“Perhaps you can divide artists into two categories: farmers and cowboys. The farmers settle a piece of land and cultivate it carefully, finding more and more value in it. The cowboys look for new places and are excited by the sheer fact of discovery, and the freedom of being somewhere that not many people have been before.”

The first time I approached Eno’s idea of the farmers and cowboys, I came at it with a newfound appreciation for the farmer—their love of craft, cultivating an idea, and extrapolating new things from the same ground is admirable. While before I may have found the farmer to be boring, I’m now totally enamored with the idea.

But with cowboys, it’s historically been an easier sell for me. When I hear about an artist who constantly switches it up, I already want to love them. There are some obvious examples—artists like David Bowie or Prince or Madonna, who famously had “different eras.” Or you could look at artists like Picasso or Da Vinci, who excelled at such different art forms and fields. These weren’t “masters of none”; they were “masters of everything.” Or at least they were bold risk-takers, unconcerned with failure. And something about taking risks—and even more so, taking big risks and succeeding—is undeniably alluring.

But I wonder, why is that? What is so appealing about someone who can shape-shift into new forms and sounds? I can’t be the only one captivated by the idea of recreation and revisioning oneself. While it certainly feels admirable to stay the course and refine your set of skills like a farmer would, the “cool” factor of the cowboy who seeks new horizons is undeniable.

I think of Octavia Butler’s often-quoted (and increasingly prescient) Parable of the Sower. Set in an apocalyptic modern USA, the protagonist Lauren Olamina forms her own religion called Earthseed, built around a central philosophy: “God is change.” For Olamina, living in a world where survival is uncertain means clinging to and embracing that idea of impermanence. The only constant is inconsistency. This idea resonated so much with readers that Earthseed has been adopted as a real religion by some.

I believe that innate within us is a sense of seeking. Our world is full of infinite unknowns, and trying to answer those questions has often propelled us forward—technologically, artistically, and as a society. You know, those big old questions like “Why are we here?”, “What is our purpose?”, “Is this real?”

Often the only way to figure something out is to just try a bunch of different things and see what works. How many people tried to fly before the Wright brothers got it right? (Shout out to the new season of The Rehearsal.) How many things did we collectively hold as truths before someone tried a new hypothesis and found a different answer? What do we hold to be true right now that will someday be proven false?

These mysteries are as vast as the universe itself. And maybe I’m getting a bit broader than I intended. I think it’s easy to do that because, in my own life, I’ve found art to be one of the best ways to try and understand these questions—even if it’s unlikely to yield clear and direct answers.

Following the work and careers of “cowboy” artists inspires me. That boldness to face the unknown again and again, to change yourself or your approach endlessly, just feels so powerful. Powerful in a world and universe where we are so small in the scheme of it all. But when an artist steps out with a new sound or a new look or a new frame of mind, it feels like the universe is shifting (even if it’s not). That’s serious power.

When I’m feeling stuck, I find so much inspiration looking toward “the cowboys.” André 3000 has been a consistent one for me. You might’ve heard by now that the enigmatic rapper, who came up as one-half of the legendary duo Outkast, has left rap in pursuit of being a flautist. It’s one of the most surprising turns this side of Frankie Muniz becoming a NASCAR driver. For years, 3000 was spotted in different locales playing his flute in public—walking down the street, at the beach, in the back of taxi cabs.

Like many, I’m sure, 3000’s story has fascinated me. And like many, I cite 3000 as my favorite rapper. Part of his magnetism came from how he punched a hole in the status quo. That he’s veered into music that’s at least adjacent to jazz (or however you want—or don’t want—to classify it) shouldn’t come as a surprise. He approached rap the way Miles Davis approached the trumpet or Pharoah Sanders wielded his saxophone—with a mind toward the future, toward new horizons, and—most importantly—to their own delight. And as I always want to clarify, his Outkast partner Big Boi is in that same category. The group’s second album branded them as ATLiens, extraterrestrial beings emerging from one of the greatest cities in the American South. They channeled astrological fates with Aquemini, kept cool with explosive production on Stankonia, and charted their own paths with their solo-double album Speakerboxxx/The Love Below. Even Idlewild, their oft-overlooked final album that doubled as a soundtrack for their own film, exemplified the group’s willingness to take creative risks as they rhymed over samples of Great Depression-era blues and jazz.

I don’t need to do a review of 3000’s whole career. Outkast broke up in 2007, and we waited 16 years for 3000 to release a solo record. When it finally arrived in 2023, he bestowed upon us 90 minutes of sprawling experimental flute recordings. The opening track’s lengthy title expresses radical candor: “I Swear, I Really Wanted to Make a 'Rap' Album but This Is Literally the Way the Wind Blew Me This Time.”

It’s that last part of the title that I think sums the cowboy idea up so well: “This is literally the way the wind blew me this time.” As an observer, when I see artists making big leaps or changes, I sometimes imagine it being a fraught decision or an intentional shift from one direction into something new. While that may be the case for some, for others it’s just a compulsion. It makes me wonder if sometimes cowboys wish they were farmers. While I can admire the willingness to go with change, it must be tough to embrace new directions and forgo finding contentment in the same place. For someone like 3000, who had years of people begging him for a solo rap album, I have to imagine there were moments where he wished he could just give that to people and feel good about it. But artistry suffers when you go against your instincts to serve a hungry market.

I also think often of Yves Tumor. In my mind, they are one of the greatest living artists. While they’ve steadily gotten more popular over the years, I’ve just been waiting for that moment when they truly break through and fulfill their destiny of being the biggest stars of their generation.

The first time I can recall hearing Yves was through the song “Limerence” on the Mono no Aware compilation. It’s still one of their biggest songs as far as streaming goes, but at this point, it’s so unlike anything else they do. It’s more or less an ambient track with a repeating, beautifully melancholic synthesizer line overlaid with the occasional sounds of thunder and a woman talking (presumably through a camera) to her boyfriend. It’s romantic, sad, sensual—a mix of emotions that are honestly hard for me to describe or pin down. But it’s overwhelmingly beautiful.

And while some of this sound still exists on a few of their earlier records like Serpent Music and Experiencing the Deposit of Faith (both of which are excellent, by the way), it wasn’t long before Yves pivoted in a far different direction. 2018’s Safe in the Hands of Love saw them emerging through a haze of trip-hop, experimental electronic music, and their devious vocals front and center. The swooning ambiance of “Limerence” was now the dark echo of an underground club.

And then, just two years later, Yves reemerged suddenly as a glam rock god. While parts of 2020’s Heaven to a Tortured Mind feel like they build off some of the experimental production of Safe in the Hands of Love, it really does feel like a new universe. It felt like a band—glitzed out and ready to erupt a stadium crowd in a chant of “this ain’t by design giiiiiiiirl.” In my mind, it’s a front-runner for best rock record of the decade—its biggest competitor being Yves’ own 2023 album Praise a Lord Who Chews but Which Does Not Consume; (Or Simply, Hot Between Worlds), which upped the glam and traded in some of the freakier experimental elements still residing in Heaven for even more '70s pastiche and '90s nihilism. What makes Yves all the more fascinating is how (again, in my opinion) their past three albums are essentially perfect—even while taking such huge swings.

Big swings are often controversial—especially in a genre like metal, where some fans hold sub-genres and stylistic boundaries as sacred. But San Francisco’s Deafheaven has never been afraid to buck convention and reimagine metal on their own terms.

I’ll admit I’m not a metalhead—I do like metal, but just “like what I like.” When Deafheaven released their landmark album Sunbather in 2013, I didn’t realize how much it was subverting norms or dividing fans. I just knew it ripped. Folding in heavy doses of shoegaze and post-rock, Sunbather is a towering, singular sound. And with that bright pink album cover, I can understand how it might have felt antagonistic even within the “blackgaze” scene they were grouped into.

That restlessness has remained central to the band’s identity. 2015’s New Bermuda leaned even further into atmosphere and beauty—my jaw dropped the first time I heard the pedal steel on “Come Back.” But 2021’s Infinite Granite might be their biggest swerve yet. For all their stylistic shifts, Deafheaven had always retained metal riffs and George Clarke’s venomous screams. On Infinite Granite, most of that disappears. What’s left is, essentially, an indie rock album—lush with melody, pop song structures, and a softness that stands in sharp contrast to their past work. And it rules. It sounds like a different band entirely, until the finale of closing track “Mombasa,” when the screaming and riffs roar back in for a cathartic, tearjerking climax.

Their newest release, Lonely People With Power (2025), flips expectations yet again—not by changing genres, but by making a straight-up metal album. After so many reinventions, it somehow feels radical to hear them go “back to basics.” Even when they return to form, Deafheaven makes it feel like a plot twist. I can’t help but admire their commitment to gut instincts and unexpected turns.

If Deafheaven’s evolution has been dramatic, SASAMI’s might be the most radical of all.

I still return to her 2019 self-titled debut all the time—still as enamored with it as I was when a friend first played it in the car. Subdued, dreary indie rock full of melody and subtle studio magic. I often reach for it on grey, low-energy days (which, in Seattle, we have plenty of). When I saw her live around that time, I was surprised at how energetic and electric she was. The music was low and moody, but her presence was vibrant.

That was maybe the only hint of what would come next—but even so, I didn’t see Squeeze coming. Her pivot to nu-metal wasn’t just bold—it was jarring. Gone was the quiet introspection; in its place came gnarly riffs, throat-shredding screams, and full-throttle 2000s hard rock aesthetics. But it didn’t feel like a gimmick. She embodied the sound fully—not as a tourist, but as a true believer.

And then, just a few weeks ago, she flipped again. Blood on the Silver Screen couldn’t be further from her last two records. It’s full-blown pop—big hooks, top 40-ready production, pulsing drum machines. Clairo even features on a track.

I’ll admit that Squeeze and Blood on the Silver Screen aren’t totally my thing—but I still find them impressive. And the more time I spend with them, the more I find to love. That’s the thing with the “cowboy.” Sometimes you prefer one version of the cowboy over another. But that doesn’t mean the artist needs to go back just to meet your expectations. I’m more excited to see where SASAMI goes next. I want to be challenged. I want her to challenge the industry.

On the final track of her debut, “Turned Out I Was Everyone,” she repeats the phrase like a mantra: “Thought I was the only one / Turned out I was everyone.” It’s hard to articulate exactly what it means, but the mood is undeniable. And that line—“turned out I was everyone”—feels like it applies to the cowboy. Cowboy artists have so many selves to share. Maybe we all do. The farmer just shows it differently. Most of us keep parts of ourselves hidden, even from people we love.

That, I think, is the core of what draws me to the cowboy spirit. It’s not just about reinvention—it’s about vulnerability. It’s about being brave enough to reveal your many selves. To pursue new paths in public. Or to pursue them at all.

I don’t think there’s a better path between farmers and cowboys. Most of us probably carry a bit of both. But Eno’s framework is a helpful way to think about creativity. Sometimes we need to be cowboys, chasing the horizon. Sometimes we need to be farmers, tending what’s already grown. Either way, the key is giving ourselves the space to make, explore, and change. The path can shift. But the pursuit—the creative life—is what nourishes us, no matter the route we take.

STRAY THOUGHTS

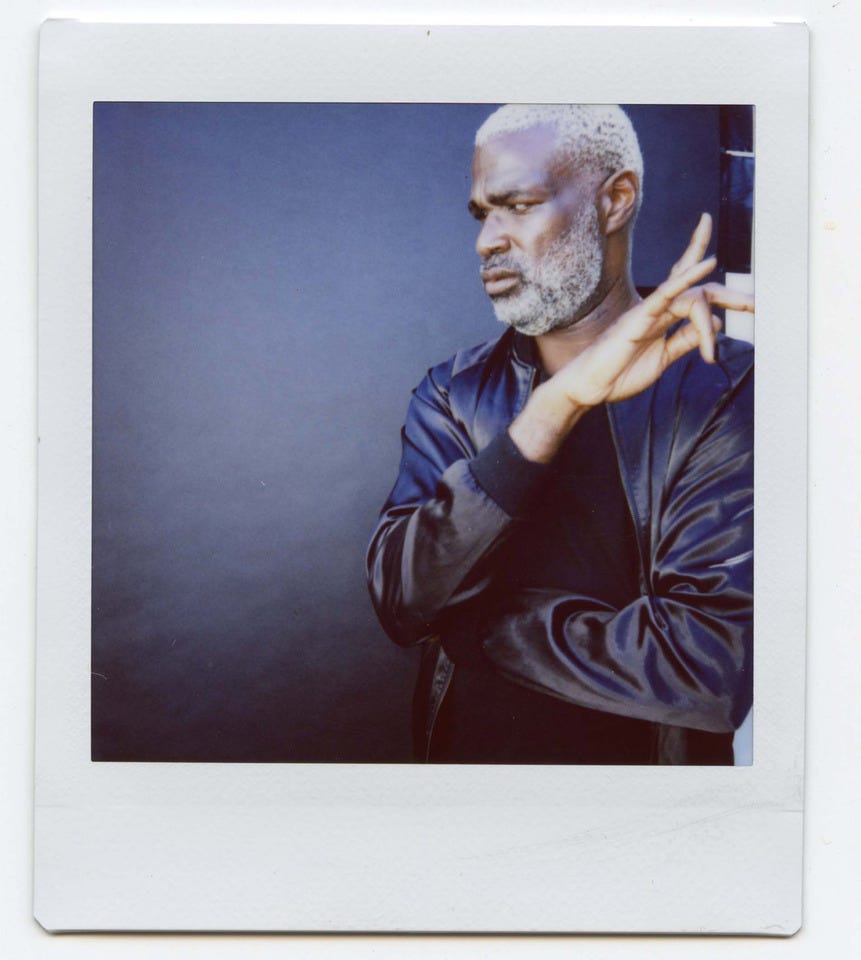

LISTENING: Tunde Adebimpe – Thee Black Boltz

Generally, I approach solo albums and side projects with lowered expectations. Whether that’s fair or not, I’m not sure. But I’ve hyped myself up plenty of times waiting for one of these projects, only to walk away a bit disappointed. So I came to Tunde Adebimpe’s debut solo album with curious ears, but I wasn’t expecting it to match the highs of his incredible work with TV on the Radio.

At first, I felt justified in my thinking. I liked it, but “it wasn’t TV on the Radio.” But that feeling didn’t last long. Over the past couple weeks, I’ve kept going back to the album. And the idea of it being “not TV on the Radio” started to feel totally irrelevant. This is a great album. Adebimpe sounds self-assured and delivers a tight set of groovy, fiery, insanely catchy songs. His voice is as tenacious as ever, and his writing feels like blazing through a science fiction novel you just can’t put down.

Special shoutout to my young kid, who’s been requesting “Magnetic” on repeat in the car going to and from school. (She also thinks the name TV on the Radio is hilarious, and laughed even harder when I told her they have an album called Return to Cookie Mountain.) “Somebody New” is easily one of my favorite songs of the year so far, with a synth line that made me sit up straight the first time I heard it. Adebimpe never lost it—of course he’s still got it.

LISTENING: Khotin – Peace Portal

Canadian producer Khotin (aka Dylan Khotin-Foote) always seems to drop something wonderful and immersive right when I need it. Over the years, he’s quietly built up one of the best catalogs in modern ambient music. His latest EP, Peace Portal, lives up to its name—six songs that feel transportive to a realm of bliss.

While not all ambient music needs to aim for “peace,” it’s a welcome feeling when it does. Khotin’s downtempo beats, soft synth pads, and tastefully mellow arrangements always help me find that centered, spacious feeling I often seek in ambient music. If you need a quick reset this week (and let’s be real—we all probably do), I highly recommend spending 30 minutes with Peace Portal and letting your mind drift.

20th Century Ambient Coming in November

My upcoming book, 20th Century Ambient, is now available for pre-order! If you’ve been enjoying the blend of music deep dives and comics in Another Thought, I think you’ll really love this.

“Through text and comics, 20th Century Ambient searches through ambient music's recent history to unearth how the genre has evolved and the role it plays in our daily lives.”

It’s out November 13, 2025 from Bloomsbury Books. Don’t miss your chance to reserve a copy now.

I enjoy your writing, Dusty. We've got to get you to Big Ears.